Acceptance Testing

Roy Miller, Software Developer, RoleModel

Software, Inc.

Chris Collins, Senior Software Developer, RoleModel

Software, Inc.

Software acceptance testing is an industry best practice.

Most development teams do it poorly. This is because teams

often misunderstand what acceptance testing is and why it

is important. Furthermore, these teams often do not have

an extensible framework for automated acceptance testing.

In this paper, we define acceptance testing and discuss

why it is important, and we describe our custom automated

acceptance testing framework.

What Is Acceptance

Testing?

Why Acceptance

Testing Is Important

A

Framework for Automated Acceptance Testing

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

What Is Acceptance

Testing?

Developers write unit tests to determine if their code

is doing things right. Customers write acceptance tests

(sometimes called functional tests) to determine if the

system is doing the right things.

Acceptance tests represent the customer's interests. The

acceptance tests give the customer confidence that the application

has the required features and that they behave correctly.

In theory when all the acceptance tests pass the project

is done.

What does an acceptance test look like? It says, "Do

this to the system and check the results. We expect certain

behavior and/or output." For example, suppose the team

is building a user interface that lists the items in an

open order. An acceptance test could check that deleting

an item is reflected correctly in the list for the order.

Why

Acceptance Testing Is Important

User stories are basically "letters of intent"

for developers and customers to work on a problem together.

They are commitments to a future conversation. The outputs

of that conversation are detailed understand of the story,

estimates of the amount of effort each task will take, intermediate

candidate solutions, and ultimately acceptance tests. Acceptance

tests are a "contract" between the developers

and the customer. Preserving those tests, running them frequently,

and amending them as requirements change, proves that there

has been no breach of contract.

Acceptance tests do three things for a software development

team:

1. They capture user requirements in a directly verifiable

way, and they measure how well the system meets those requirements.

2. They expose problems that unit tests miss.

3. They provide a ready-made definition of how "done"

the system is.

Capturing Requirements

We agree that understanding user requirements is critical

to the success of a project. If your system doesn't do what

users want, it may be technically elegant but practically

worthless. The problem is in assuming, as many methodologies

do, that exhaustive specifications will help.

One study showed that typical requirements specifications

are 15% complete and 7% correct, and that it was not cost

effective to complete or correct them [1]. There is strong

support for the idea that exhaustive requirements specifications

are impossible. Even if exhaustive specifications were possible,

they do not guarantee that your system will do what users

want. Perhaps worst of all, you also cannot verify those

specifications directly. On most projects, someone still

has to translate those specifications into use cases and

test cases. Then either an army of testers execute those

tests and document results, or your customers have to do

the job.

Acceptance tests address both issues. First, acceptance

tests can grow as the system grows, capturing user requirements

as they evolve (which they always do). Second, acceptance

tests can be validated directly - if a test passes, the

system meets the user requirements documented in that test.

Unless you can verify directly that your software does what

users want in the way they want it done, you cannot prove

that the system works. Acceptance tests provide that validation.

Beck says in Extreme Programming Explained,

“Any program feature without an automated test simply

doesn't exist” [2].

We agree with the sentiment, and we believe automation

is wise. However, it is important to note that having acceptance

tests is more important than automation.

System Coverage

In Testing Fun? Really?, Jeff Canna describes acceptance

(or functional) tests this way:

"Unit tests alone do not give the team all the confidence

it needs. The problem is, unit tests miss many bugs. Functional

tests fill in the gap. Perfectly written unit tests may

give you all the code coverage you need, but they don't

give you (necessarily) all the system coverage you need.

The functional tests will expose problems that your unit

tests are missing" [3].

Without acceptance tests, your customer cannot have confidence

in the software. In the end, the developers cannot either.

All the classes might "work", but a business transaction

might not do what the user wants. You will have engineered

a fine house nobody wants to live in.

Knowing When You're Done

How do you know when your system is "done"? Many

software development teams say they're finished when time

runs out, or when they think they've caught all of the bugs.

Acceptance testing gives you a better yardstick than that.

Your system is done when it is ready for release. It is

ready for release when the acceptance tests deemed "must-have"

by the customer pass. No other definition makes sense. Your

system is not done when you have written all the code, or

run out of time or money. What does "seventy percent

done" mean? Without acceptance tests, you have to guess.

With a maintainable suite of acceptance tests that you run

automatically on a daily basis, you can know without doubt

how done you are at any point.

How To Do Acceptance

Testing

Acceptance testing sounds simple, but it can be a challenge

to do it right. The major issues to address are who writes

tests, when they write tests, when tests are run, and how

to track tests.

Who Writes the Tests

The business side of the project should write tests, or

collaborate with the development team to write them. The

"business side" of the project could be the XP

customer, other members of the customer's organization (such

as QA personnel, business analysts, etc.), or some combination

of the two. The XP customer ultimately is responsible for

making sure the tests are written, regardless of who writes

them. But if your project has access to other resources

in your customer's organization, don't waste them!

Business people should be able to write them in a language

that they understand. This metalanguage can describe things

in terms of the system metaphor, or whatever else makes

the customer comfortable. The point is that the business

people should not have to translate their world into technical

terms. If you force them to do that, they will resist.

When To Write the Tests

Business people should write acceptance tests before developers

have fully implemented code for the features being tested.

Recording the requirements in this directly verifiable way

minimizes miscommunication between the customer and the

development team. It also helps keep the design simple,

much as writing unit tests before writing code does. The

development team should write just enough code to get the

feature to pass.

It is important for business people to write tests before

the "final product" is done, but they should not

write them too early. They have to know enough about what

is being tested in order to write a good test. More on this

in "How We Have Done Acceptance Testing" below.

When To Run the Tests

Tests should be able to run automatically at a configurable

frequency, and manually as needed. Once the tests have been

written, the team should run them frequently. This should

become as much as part of the team's development rhythm

as running unit tests is.

Tracking the Tests

The team (or the Tracker if there is one) should track

on the daily basis the total number of acceptance tests

written, and the number that pass. Tracking percentages

can obscure reality. If the team had 100 tests yesterday

and 20 passed, but they have 120 today and 21 pass, was

today worse than yesterday? No, but 20% of the tests passed

yesterday and 17.5% pass today, simply because you had more

tests. Tracking numbers overcomes this problem.

How We Have Done Acceptance Testing

At the client where we have been doing acceptance testing

longest, we have seen acceptance testing proceed as follows:

1. The XP customer writes stories.

2. The development team and the customer have conversations

about the story to flesh out the details and make sure there

is mutual understanding.

3. If it is not clear how an acceptance test could be written

because there is not enough to test it against yet, the

developer does some exploration to understand the story

better. This is a valid development activity, and the "deliverable"

does not have to be validated by an acceptance test.

4. When the exploration is done, the developer writes a

"first cut" at one or more acceptance tests for

the story and validates it with the customer. He then has

enough information to estimate the completion of the remainder

of the story. He runs the test until it passes.

5. Once the customer and the developer have agreed on the

"first cut" acceptance test(s), he hands them

over to business people (QA people on our project) to write

more tests to explore all boundary conditions, etc.

We have found this highly collaborative approach to be most

effective. Developers and business people learn about the

system, and about validation of the system, as it evolves.

Stories evolve into acceptance tests. Many stories require

only one test, but some require more. If developers get

the ball rolling, but the customer ultimately drives, things

seem to work better.

A

Framework for Automated Acceptance Testing

Writing a suite of maintainable, automated acceptance tests

without a testing framework is virtually impossible. The

problem is that automating your acceptance testing can be

expensive.

We have heard it suggested that the up-front cost for software

testing automation can be 3 to 10 times what it takes to

create and execute a manual test effort [4]. The good news

is that if the automation framework is reusable, that up-front

investment can save an organization large sums of money

in the long run.

In a nutshell, we saw a market need here. If we had a reusable

automated acceptance testing framework that we could use

on our projects, we could save our customers money and increase

the verifiable quality of our software. For example, one

of our customers is subject to regulatory approval by the

FDA for all software systems. We anticipate that having

automated acceptance testing in place will reduce the time

for FDA validation at this client from five months to several

weeks (more on this in "How We Have Used Our Framework"

below).

Why We Built Our Own Framework

It would be nice to find a JUnit equivalent for acceptance

testing, but we have not found it yet. There are many products

on the market to facilitate acceptance testing. They suffer

from two problems:

1. They do not test enough of the system.

2. They are not extensible.

Existing record/playback tools test user interfaces well.

Other tools test non-user interface services well. We have

not found a tool that tests both well.

Existing tools also suffer from the "shrink wrap"

problem. They may be configurable, but they are not extensible.

If you need a feature that the product does not have, you

have two options. You can hope they include it the next

release (which is probably too late for your project), or

you can build your own feature that interacts with the off-the-shelf

product in a somewhat unnatural way.

We wanted a tool to test user interfaces and other modes

of system interaction (such as a serial connection to a

physical device). We also wanted the ability to modify that

tool as necessary to reflect the lessons we learn about

testing. So, we chose to build our own acceptance testing

framework to support testing Java applications.

An Example of How To Use the Framework

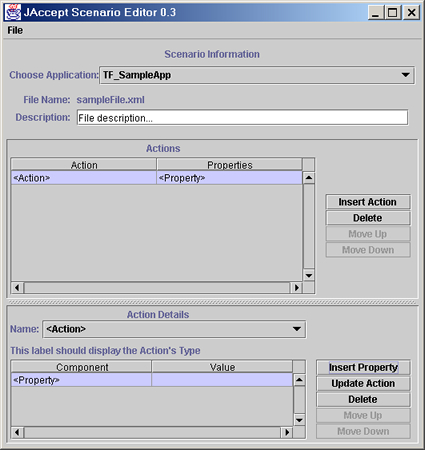

The following screenshot of our JAccept™ Editor (Figure

1) should help you follow this example.

Figure 1: JAccept™ Editor screenshot

Suppose the development team is adding a story to track

orders to an existing application. The team calls it Order

Tracker. The story has a user interface with a text field

to enter a customer ID. When a user hits the Find Customer

button, the application queries a database for open and

fulfilled orders for that customer and displays them in

a scrolling list. When the user clicks on an order in the

list, the application displays details for that order at

the bottom of the window.

The team is just starting a new iteration. How would the

team use our automated framework to create and execute acceptance

tests for the Order Tracker story?

Setting Up the Environment

The customer meets with a developer and a business person

to discuss the new story. The business person has some experience

writing tests with our JAccept™ framework, so the mechanics

are not a problem. After a brief discussion, the developer

does some exploration to determine how he might implement

the story. He writes a first cut of an acceptance test to

validate it, and he runs the test to make sure the script

will test the known interaction points. Part of that exercise

is to modify the JAccept™ framework to recognize the

new "application" that will be added to the system,

but just enough to allow tests to be written.

Creating the Test

The developer now has enough information to estimate his

tasks. He gives the QA person the initial acceptance test

to serve as a pattern for the QA person to expand upon.

He will need to be collaborating with the developers to

make sure they know when things aren't working as desired,

and with developers and business people to make sure they

are testing the right things.

He opens the JAccept™ Editor (see Figure 1 above).

He chooses "Order Tracker" from a combo box listing

available applications to test. Then he adds some Actions

that will interact with the Application programmatically

to determine if the it behaves as required. He adds an "Enter"

Action to populate the "Customer ID" text field.

For that Action, he adds a Property to put a valid customer

ID in the field. He then enters the following additional

Actions with the appropriate Properties:

-

A "Click" Action to click the "Find

Customer" button

-

A "CheckDisplay" Action to confirm that the

order list contains the expected number of orders

-

A "Click" Action to select the second order

in the list

-

A "CheckDisplay" Action to confirm that the

appropriate details are displayed

When he is done entering Actions, he clicks the "Save

Scenario" button. The JAccept™ framework creates

an XML file to represent the Scenario.

Running the Test

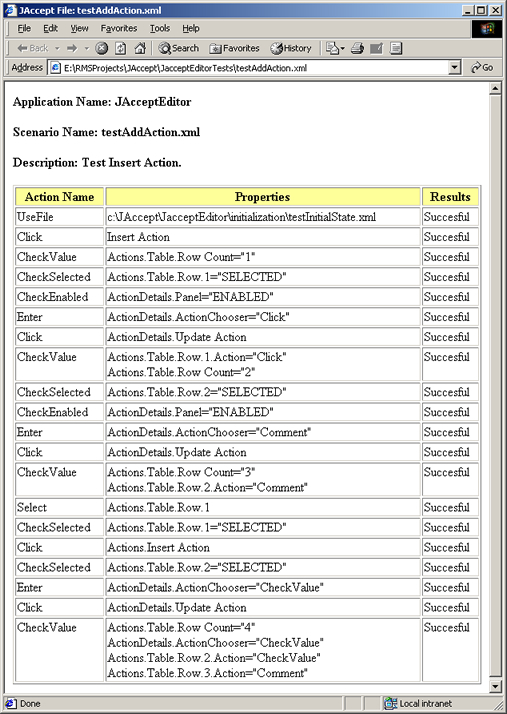

At midnight, a batch job starts up the framework. It cycles

through all of the Scenario files in the input directory,

processes them, updates the results for each Action in each

file, and creates an XML output file.

Verifying the Test

The next day, the customer opens his web browser and checks

the output, formatted by an XSLT. The XSLT added a column

to file to display whether a particular Action row passed

or failed. The "CheckDisplay" Action row failed,

and the failing Properties are highlighted. The customer

talks to his developer partner and determines that he did

not make an error in writing the test. The developer takes

ownership of the bug and fixes the offending code. The QA

analyst reruns the test manually to see if the fix worked.

Key Points

Note some interesting things about this description:

1. The customer (in cooperation with the developer) writes

the test before the development team implements the story.

2. The customer creates Scenarios in a language he can understand

(Actions and Properties).

3. Once the application is defined to the framework, the

customer can create tests to cover any permutation of Actions.

4. The tests can run automatically at a configurable frequency.

5. Anybody can run the tests manually at any point.

The Kernel

We built the JAccept™ framework around five core concepts:

1. Scenarios, which are structured list of Actions.

2. Actions, which specify something in the application

to be interacted with (e.g. input from a serial port) and

what to do there (e.g. parse the input).

3. Properties, which are key/value pairs that specify

a name for something in the application to be interacted

with and the value to set there or the value to expect from

there.

4. Strategies, which encapsulate the things in the

application that can be interacted with, and can perform

valid actions on those things programmatically.

5. An Interpreter, which loops through all the Actions

in a Scenario and uses reflection to determine the application

things to execute each Action on and the values to set or

check.

The JAccept™ suite of tools includes an editor that

allows a user to create and edit Scenarios, enter/delete/reorder

Actions in those Scenarios, and enter/delete/reorder Properties

for each Action. The framework converts Scenarios to XML

when a user saves them from within the JAccept™ Editor.

The framework uses a utility class called the ScenarioBuilder

to load Scenarios from XML files. When a user opens an existing

Scenario within the editor, the ScenarioBuilder uses an

XML SAX parser to build an in-memory Scenario instance that

the framework can use. Scenario files look like this, which

tests the JAccept™ Editor itself:

Figure 2: JAccept™ XML Input File

The framework supports running Scenario files individually

or in groups. The JAccept™ Runner user interface allows

a user to choose a directory and run all the files there,

or pick single file to run. When the user clicks the "Run"

button, the framework executes all of the selected input

files and shows a running count of files executed, files

that passed, and files that failed.

Once all the files have been run, the JAccept™ Runner

window lists files that failed. A user can click on any

file in the list and display the output in a browser, formatted

with an XSL style sheet.

Defining Applications To the Framework

Developers have to define new applications to the framework

before tests can be run against them. Defining an application

involves the following:

-

creating a Context class for the application which

contains an instance of the application to test

-

creating new Actions/Strategies as necessary

-

adding the new application to the existing Application

Dictionary in the framework

This setup effort could take anywhere from one-half day

to a few days, or even longer, depending on the complexity

of the application.

The Context

for an application holds an instance of the application

to be tested. It also defines the "root strategy"

for the application (more on this below). Here is the Context

for a sample application named TF_SampleApp:

import java.awt.*;

import com.rolemodelsoft.jaccept.*;

import

com.rolemodelsoft.jaccept.strategies.*;

import javax.swing.*;

public class TF_AcceptanceTestContext

extends TF_AbstractAcceptanceTestContext

{

protected TF_SampleApp

sampleApp =

new TF_SampleApp();

protected JFrame frame

= new JFrame();

}

protected void initialize() {

frame.setContentPane(sampleApp);

}

protected ViewStrategy

getDefaultRootStrategy()

{

return new TF_SampleAppViewStrategy(sampleApp);

} |

Listing 1: Context for TF_SampleApp

The ViewStrategy

for an application defines a map of strategies for each

of the components of the application to be interacted with

programmatically. The ViewStrategy

for TF_SampleApp

looks like this:

import javax.swing.*;

import

com.rolemodelsoft.jaccept.strategies.*;

import

com.rolemodelsoft.jaccept.strategies.swing.*;

public class TF_SampleAppViewStrategy extends AbstractCompositeViewStrategy

{

protected TF_SampleApp sampleApp;

}

protected ViewStrategyMap defaultSubViewStrategyMap()

{

ViewStrategyMap map =

super.defaultSubViewStrategyMap();

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButton1()));

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButton2()));

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButtonMinus()));

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButtonPlus()));

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButtonEquals()));

map.put(new ButtonViewStrategy(sampleApp.getJButtonClear()));

map.put(new TextFieldViewStrategy("display",sampleApp.getJTextField()));

return map;

}

|

Listing 2: ViewStrategy for TF_SampleApp

The ViewStrategyMap for TF_SampleApp

defines a hierarchy of strategies for each widget (in this

case) to be interacted with programmatically. Each of those

strategies holds an instance of the widget to be tested,

and defines the programmatic interaction behavior to be

executed when the JAccept™ framework interacts with

it. A Swing ButtonStrategy,

for example, looks like this:

import javax.swing.*;

import com.rolemodelsoft.jaccept.utilities.*;

public class ButtonViewStrategy

extends ComponentViewStrategy {

protected AbstractButton button;

}

public void click() {

if (!button.isEnabled())

throw

new RuntimeException("Unable to click the button

because it is disabled.");

button.doClick();

} |

Listing 3: ButtonStrategy for TF_SampleApp

The standard set of Strategies in the framework is rather

comprehensive, especially for standard Swing components,

but it does not cover every possibility. Although the time

to create new strategies can vary, most new strategies require

about an hour to create. This would increase setup time

by one hour per new Strategy.

Extensions

We are still working on extending the JAccept™ framework

to support testing web applications. This includes integration

with HttpUnit, additional Strategies and Actions for web

page "widgets", etc. We have been busy with others

things in recent months, so we haven't completed this task.

In the future, we plan to extend the framework to support

testing for small spaces (cell phones, PDAs, etc.). One

of the authors (Chris) created a unit testing framework

for J2ME applications that we might reuse entirely or in

part to support this extension.

How We Have Used Our Framework

The JAccept™ framework arose out of the need one our

customers had to verify their new software for regulatory

approval by the FDA. The typical verification period is

roughly five months. The client has not released yet, but

we anticipate that JAccept™ will reduce this verification

period to several weeks.

Two "validators" from the internal testing organization

write acceptance tests at this client. The team tracks the

pass/fail percentage and the development team fixes bugs.

The client plans to use the documented output from JAccept™

to satisfy FDA regulatory requirements.

Our experience with applying JAccept™ at clients is

not large, so we are careful not to extrapolate too far.

Based on this experience, though, we have found the following:

-

This client has been willing to contribute people from

their existing testing organization to write tests.

They used to do this anyway. Now they don't have deal

with the mundane and error-prone exercise of running

the tests.

-

If we want the business side of the project to use

the tool at all, ease of use is a must.

-

Non-QA people resist writing tests, no matter how easy

the tool is to understand.

We also encountered other issues:

-

It was difficult to get developers, the QA organization,

and other business people in synch about acceptance

testing. As a result, the framework was developed late

in the project.

-

The customer has an established testing organization

that is new to XP. It was difficult to establish effective

collaboration between that group and the development

team.

-

It has been difficult to write tests at the right time

so that they are not as volatile.

There was little we could do about the first issue. The

alternative was not to have an acceptance testing framework.

We believe creating the framework was worth it in the short

and long term.

The second issue also was unavoidable. Once the QA organization

and the development team ironed out the collaboration issues,

the process started to run smoothly. Now, both groups work

together effectively.

The third issue was a simple matter of having the team

learn. In the beginning, it was difficult to know when to

write tests. If the team wrote them too early, based on

certain assumptions that turned out to be wrong, it was

a big effort to go back and modify all of the tests. There

cannot be hard and fast rules about this.

Conclusion

Acceptance testing is critical to the success of a software

project. An automated acceptance testing framework can provide

significant value to projects by involving the customer,

and by making acceptance testing part of an XP team's development

rhythm. The initial investment of time and effort to create

such a framework should pay off in increased customer confidence

in the system the team builds. This is one of the keys to

customer satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We knew acceptance testing was critical to our project's

success, so we wanted to do it right. We hired Ward Cunningham

to help create the first iteration of the JAccept™

framework over one year ago. The framework has grown significantly

since then, but it would not have been possible without

some of his ideas.

Many thanks to the rest of the RoleModel software team

for their comments and suggestions on this paper. Specifically,

thanks to Adam Williams, Ken Auer, and Michael Hale for

technical input, and to Jon Vickers for research help.

References

1. Highsmith, J. Adaptive Software Development, Information

Architects, Inc. (2000), presentation at OOPSLA 2000 quoting

a study by Elemer Magaziner.

2. Beck, K. Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change,

Addison Wesley (2000).

3. Canna, J. Testing Fun? Really?, IBM developerWorks Java

Zone (2001).

4. Kaner, C. Improving the Maintainability of Automated

Test Suites, paper presented at Quality Week '97 (1997).

Revision History

|